re-mapping cultural data of the sixties folk music revival digitally through virtual reality, spatial analysis, network analysis & other digital humanities tactics.

News

Reports from the Revising Humbead’s Project.

Principal Investigator

Michael J. Kramer

Overview

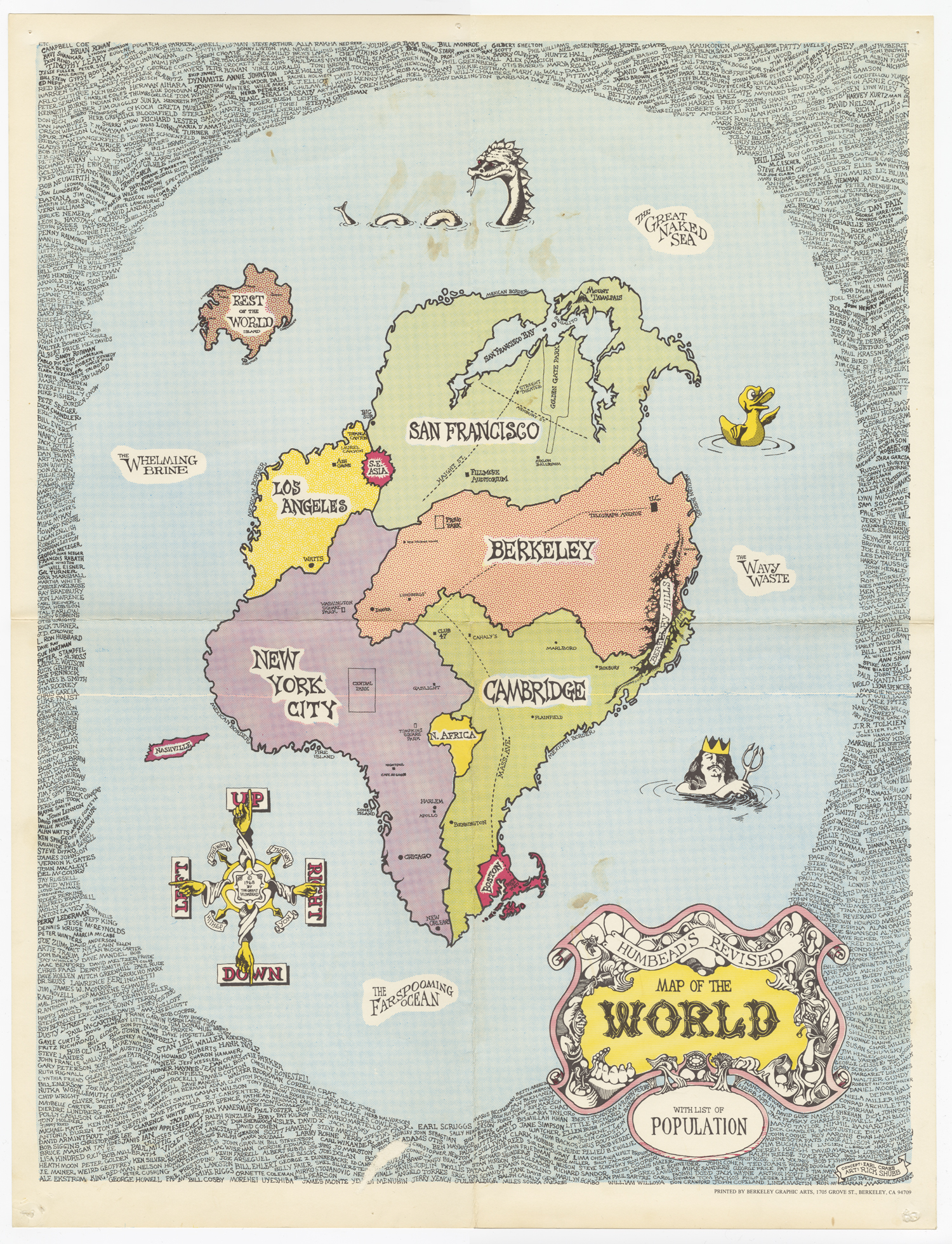

Humbead’s Revised Map of the World reimagines the globe from the perspective of the West Coast folk scene and emerging hippie counterculture. First printed in 1968, with subsequent iterations produced in 1969 and 1970, it was created by Rick Shubb and Earl Crabb, two Bay Area folk music aficionados. Like Saul Steinberg’s famous New Yorker magazine cover View of the World from 9th Avenue, published a few years later in 1976, Humbead’s is meant to be a humorous artifact, but also a serious one. It is seriously funny, we might say. Shubb and Crabb cartographically distort Euclidean space and Mercator projection in order to suggest a more perceptually and culturally accurate “mattering map.” It is also rich with data, not only including many places, but also over 1000 names in its “population,” written in tiny print around the edges of the map. Some of the names are expected, but others quite surprising. Pete Seeger, Joan Baez, Bob Dylan, sure, but Charlie Chaplin and Bugs Bunny? Why are they included in the population of Humbead’s Revised Map of the World?

Typically, digital humanities projects have sought to visualize data using maps; how, in this case might we reverse the process, exploring the data contained in a map? Moreover, how might we use a range of digital tactics to investigate the full humanities significance of Humbead’s and mattering maps similar to it? This project uses spatial, data, and network analysis as well as virtual reality and potentially digital animation to seek better understandings of how a historical “mattering map” mattered. It also investigates how digital public history can present a historical artifact effectively, in all its richness of meaning, to general audiences.

The Original Revision

On the original 1968 version of the map, graphic designer Shubb and conceptualizer Crabb (later a pioneering computer programmer) display key sites of the 1960s urban folk revival as a playful Pangaea. Locations such as Greenwich Village in New York City, Berkeley in California, and Cambridge, Massachusetts are large, while the “Rest of the World” has been moved to a small island on the margins. Key neighborhoods, performance venues, and public locations appear more prominently, sometimes whimsically placed. The idea for the map originated in 1967 when Crabb remarked to a hitchhiker from Berkeley to Kansas City that he should ask for rides to New York City since it was closer to Berkeley than Kansas City and Shubb heartily agreed.

The two folk revival enthusiasts (Shubb a musician, instrument builder, and graphic artist; Crabb an influential listener on the scene) met a few nights later and continued to map out their new visual representation of their world. “Socially, if not geographically, it felt just as valid as a ‘real’ map,” Shubb remembers in his memoir. They added places, debated how to portray the relationships among them, and decided to add names so that people might notice that they were included on the poster and purchase it in a local bookstore, instrument shop, or record store. Many did purchase the map. It went through three printings at least. They would spend hours lingering over its many details, smiling at its inside jokes, and pondering, maybe even debating its ideas of how the world “really” existed for those swept up in the folk revival as seen from Northern California.

Revising the Revision Digitally

As Rick Shubb remarks, “If there were some way of tracking stats on a printed poster like there is for a web page, I’m sure it would rank high on the list of total viewing time logged. Because it would hold your eye for an unspecified time, and held up to repeated viewing.” This folksy, analog, whimsical map already proposes and presages computational, digital, and serious (as well as seriously funny) revisions. How might we bring its humor, its meanings, its significances forward for exploration by digitizing it?

Early documents about and sketches of the map exist in the Earl Crabb Collection at the American Folklife Center. They can be included in a digital curation of Humbead’s to document the map’s development. So too can two later versions (the 1969 map adds more names; Shubb completely redesigned the 1970 version). A dynamic digital design might allow the viewer to overlay these different versions and explore correlations and distinctions among them.

Humbead’s Revised Map has another quality too: not only is it full of intriguing geographic reimaginings, it is also extraordinarily rich with historical data. The mix of names on the map suggest the need for annotation, contextualization, and network analysis. “I tried to make unlikely combinations and clusters,” Shubb explains. “When someone first encountered the map, they typically would first be amused by the ‘countries’ (Berkeley, NY, SF, etc.), but then if it held their attention long enough, they would spot a familiar name among the swarm of names, and their eye would start to meander. Pretty soon they would be reading aloud odd combinations, and smiling.” Following Shubb’s lead—a kind of remix offered in the original map itself—digital revisions of Humbead’s Revised Map of the World digitally offer a promising way to study how Shubb arrived at his comic arrangements of the networks of participants who constituted the musical and cultural folk revival on the West Coast in the 1960s. What is a music “scene” and how does comic association (and perhaps also disassociation!) help to form it?

Indeed, for scholars and general audiences alike, digital analyses of Humbead’s Revised Map of the World are full of potential discoveries. This is particularly the case in terms of the understudied 1960s West Coast folk music revival. Most histories privilege the East Coast and Southern facets of the folk revival story, concentrating on when Bob Dylan went electric at the Newport Folk Festival in 1965 or the sectarian leftist political ideologies that saturated the folk revival in New York City or the obsession with Southern rural culture among young urban elites in the East and Midwest. Humbead’s Revised Map, as its name suggests, offers a different mapping of the revival. On the West Coast, the binaries of old and new, rustic and futuristic, premodern and postmodern possessed their own peculiar dynamic. The Northern California economy of the post-World War II decades, for instance, was perhaps the epicenter of the military-industrial complex. Silicon Valley erupted directly out of orchards and farmlands with no intermediary steps from an agricultural to a post-industrial economy and a potent mix of governmental and commercial partnerships. This new economy arose in a setting of postwar abundance, but it also grew on top of older traditions in Northern California of bohemianism and radical politics. Did the distinctiveness of the West Coast scene shape the imaginings of Humbead’s, its content and its tone. Here, as Jesse Jarnow suggests in his book Heads, was not only a map of the folk revival, but also a psychedelic evocation of the emerging late-sixties counterculture.

This is all very serious stuff; however one of the key aspects of Humbead’s Revised Map of the World is that it is meant to be very funny. Digital humanities projects rarely address or dissect humor. How might we do so effectively, in an inclusive mode that welcomes people in to the joke? This remapping of Humbead’s Revised Map seeks to bring this humor to the surface. Why, for instance, was it funny to place Charlie Chaplin and Bugs Bunny in this folk music revival population? What did that signal? Why did the map imagine Telegraph Avenue in Berkeley running directly into Mass Ave in Cambridge, Massachusetts? Humbead’s was meant to elicit chuckles from those in the know. It was a way in to the folk scene for those who sought to get the gags. It signaled an emergence of an underground scene to the surface of American culture. Digital re-representations might catch this tone and energy through virtual reality explorations of the map and digital animation storytelling about its contents. Virtual reality allows one to step in to the map itself, inhabiting its virtual world, discovering its content, form, and suggestive meanings directly through virtual interaction. Digital animation storytelling can bring out the map’s many details for a broader public audience, positioning its spatial representations in more narrative forms.

Mapping Out Technological Challenges for Digital Humanities and Digital Public History

Humbead’s poses particular technical challenges. How do we create effective digital interface design for moving between the maps scalar oscillations. At one moment the eye takes in the large-scale geographic space collapsed into a new “Map of the World”; at another, one zooms in on details, entering into the microscopic specifics the map presents. How does a computer user navigate between these different levels effectively? How do we zoom in and zoom out to catch the spatial experience of gazing at Humbead’s?

Another issue might be how we further historicize Humbead’s? How do its design compare to other versions of the map itself, from the early sketches to later revisions by Shubb? How, for that matter, does Humbead’s map on to other folk revival mattering maps: Dorothea Dix Lawrence’s Folklore Music Map of the United States, made in 1945, or Alan Lomax’s Global Jukebox project, emerging in the 1980s and 90s? In terms of contextualization, how might a digitized revision of Humbead’s incorporate other archival sources, such as a 1968 Berkeley Barb article that comically describes the creation of the “Charchild-Denson Identifier of Humbead’s List of the World’s Population”? Can digital navigation dramatize the interplay between immersive experiences of the folk revival and historical contextualizations of it that link up multiple related artifacts and sources?

The map also poses technical challenges for displaying multimedia annotations of the many names on it: how does one store, link, and keep up to date multimedia to details on the map in a useful interface? Does one attempt to draw from linked open-source data on the web (Wikipedia, sound libraries) or is it more effective to create an independent database of fair-use clips of sound and image? How does one design this database of annotative information and metadata to generate a robust framework for exploring relationships and networks represented on the map? If existing tools are not adequate, how do we begin to address revisions to them or is new software required?

Revising the Research Questions

- Can we experiment with interface design and interactive navigational approaches that dramatize the map’s many components, revising the map’s representations yet again, so that the historical significance of this artifact emerges more robustly through iterative, interactive versioning?

- Can existing mapping and visualization tools (Mirador, ArcGIS, Topotime, Neatline, Storymap.JS, IIIF) support these aims or are new tools required?

- How do we address the challenge of annotating Humbead’s Map‘s dense, detailed information digitally for analysis and for display?

- How might we add multimedia elements to the map to enrich the artifact through sonic, visual, and textual associations? If one hovers over a certain region on the map, can one hear folk music associated with that place? Can we, in this sense, return the map to the music that inspired it?

- How might we conduct network analysis of the map’s “population” through developing a data set of performer locations, birthplaces, musical styles, and other factors that allow us to re-map Humbead’s Revised Map of the World?

- How might digital animations of the map narrativize its spatial representations, evoke its graphic style, and unfold its many details, meanings, and significances?

- What would it mean to create a virtual reality of this imaginary world? Could virtual reality provide access to the historical perceptions and realities that produced the original revised map by allowing a user to step in to the map itself, virtually? Could virtual reality also produce new ways of experiencing the mattering in this “mattering map” for both aficionados and newcomers?

Provisional Conclusions

Digitally revising Humbead’s Revised Map of the World—exploring its components, its conceptualization, its visual presentation, its sense of place and meaning—has the potential to foster fresh insights into the folk music revival’s history and modern American cultural history more broadly while also providing a model for other digital humanities and digital public history projects. Messing around with the map digitally, we can enter into its mappings more profoundly and effectively.